Europeans want their olive oil to be natural – extra virgin – and from Italy. That’s the quality European customers are willing to pay for.

About 80 million liters of Italian extra virgin olive oil are sold every year alone to Germany, according to official statistics. Large parts of the oil is neither extra virgin, nor from Italy, however.

According to our investigation, these oils can be industrially adulterated. They can be put together from multiple Mediterranean countries, oils of different qualities and origins, mixed to create an “extra virgin” olive oil.

Fabio Lattanzio is a lab technician expert in analysis of olive oil. He comes from Apulia, in the South of Italy. For over nine years, Lattanzio worked as an analyst in a one of the largest intermediary companies of olive oil in Italy, Azienda Olearia Valpesana, located in Tuscany. On December 19th 2011, he quit his job.

The company, Valpesana, is accused of commercial fraud – adulteration of olive oil – in the largest European criminal investigation ever into the olive oil trade. Lattanzio speaks openly about the dirty olive oil trade. His ex-colleagues are now being prosecuted. “I didn’t want to be part of what I considered a criminal network,” he said.

For decades now fraudsters have been mixing inferior olive oils from different countries – often using illegal methods. Mixing oil is not a problem in itself, the craft of oil producers lies in their ability to create good and stable mixtures. But the very same skill allows dishonest producers to hide oil with inferior quality and sell it as extra virgin.

Fraudulent producers sell their adulterated oils all over the world and to almost every supermarket in Germany – under false labels of origin and quality. Customers are denied the chance to know what’s in the oil they bought.

Without whistleblowers from the inner circle, investigators have no chance to come after these people. Product tests usually do not work to detect the fraud. Chemical experts create sophisticated mixtures after special recipes so there is no way to find out how these oils were mixed together.

“If we only had analyzed the olive oil, we would have never been able to uncover the fraudulent system,” said Prosecutor Aldo Natalini, the coordinator of the criminal investigation against Valpesana, during a meeting with Interpol in Madrid. ↓↓

The Center of the Fraudulent Network

Investigators uncovered the biggest olive oil fraud ever only because of Lattanzio’s testimony and accidental findings of secret recipes. We obtained these recipes. The trace is leading right into the shelves of REWE.

Valpesana is one of the most important olive oil traders in the world, and through middlemen and bottlers it sold its olive oil mixtures to many German supermarkets.

The Valpesana investigation reveals an alleged widely connected system of fraud. Not every drop of Valpesana’s oil was adulterated, but it was a major hub for the industry. Manufacturers seem to be breaking every rule, thinking that they won’t be caught. And who – even when the evidence is damning – still think that they have committed no wrongdoing.

Documents and protocols of wire-tapped phones give rise to doubts over the quality of some of Valpesana’s mixtures of extra virgin oil, Germany’s favorite category with a 98 percent market share.

Unfortunately, extra virgin oil is a malleable product and especially vulnerable to fraud.

The high demand creates pressure. Market leaders don’t press olives anymore. The intermediary trade is much more lucrative than the production itself. Middlemen have an annual turnover of hundreds of millions of Euros – and have been involved in scandals many times.

Two decades ago Domenico Ribati sold Turkish hazelnut oil and labeled it as Italian oil. He was sentenced 13 months on parole. Another company did the same with Tunisian olive oil.

One of the largest criminal investigations of the sector was held six years ago. The Azienda Olearia Basile from Apulia allegedly sold three million liters of olive oil from Spain, Greece and Tunisia as “100 percent Italian” while some of it was even labelled “organic”, although it was obtainedthrough conventional agriculture. The trial is ongoing.

For a long time there was no European regulation for middlemen who bought different oils, mixed and resold them. The EU commission adopted the first olive oil regulation in 1991. Since then the regulation changed 24 times. Meanwhile there are guidelines oil manufacturers have to follow. These guidelines are in place to secure the “purity and quality” of the oil. There are limit values, lab tests and experts who taste the oil and evaluate its harmony.

But according to our investigation this system doesn’t work. The fraudsters just changed the way they produced their adulterated oil to get past the new regulations. The limit values of the EU now serve as manual for the fraudulent olive oil. The Valpesana case shows how these companies circumvent the EU regulations.

The Guardia di Finanza, an Italian police unit specialized in economic fraud, started the investigation on Valpesana in April 2011, just with a random check. Back then Valpesana was making an annual turnover of 200 million Euro and was selling 65.000 tons of olive oil per year. That’s over 15 percent of the whole annual Italian olive oil production.

Monteriggioni is a small village close to Siena, surrounded by small hills. There are olive oil trees, woods and meadows. A peaceful spot, no one would think of any fraudsters around here. The company’s factory is located at an outward road, lined with cypresses. But during a raid, investigators found a hot lead Valpesana’s laboratory: secret recipes for the mixtures the company used for the alleged oil adulteration.↓↓

INTERVIEW

with the principal witness against Valpesana

Customers: Defrauded Twice

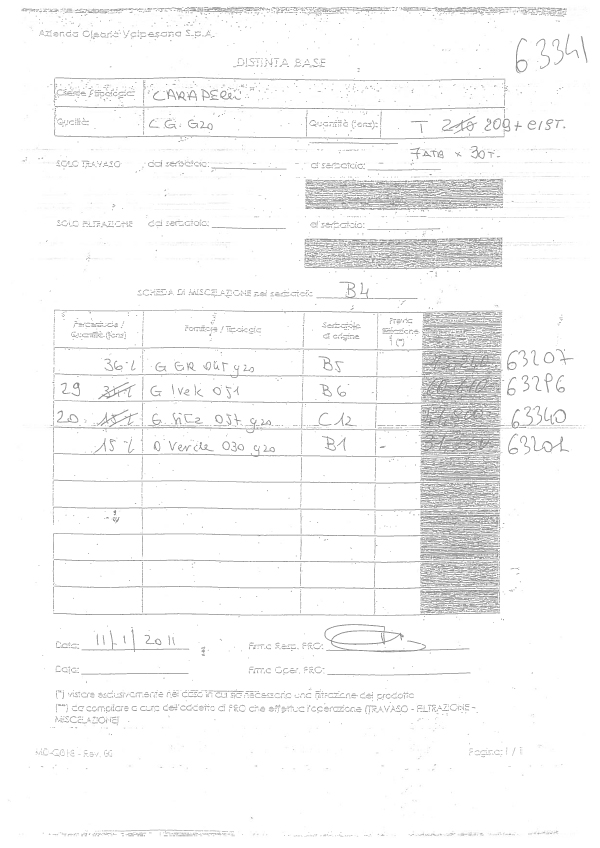

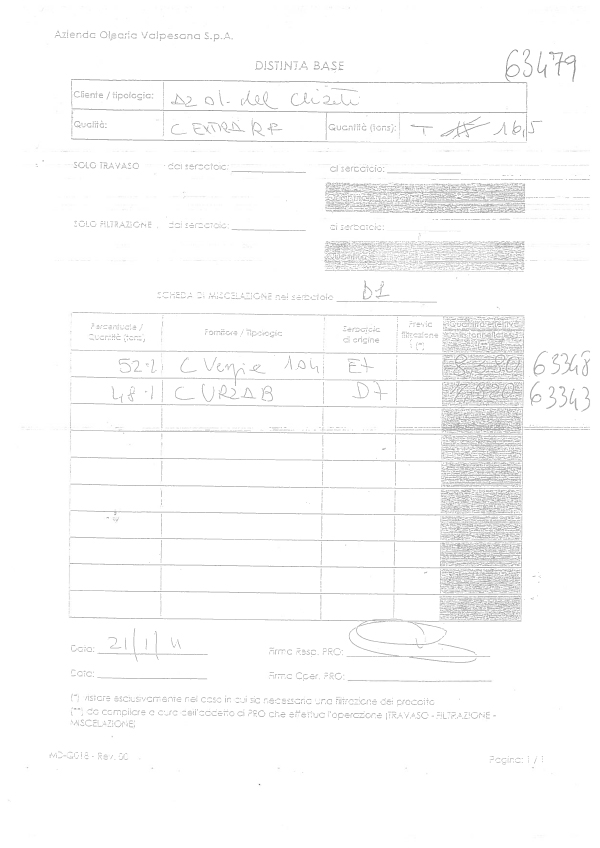

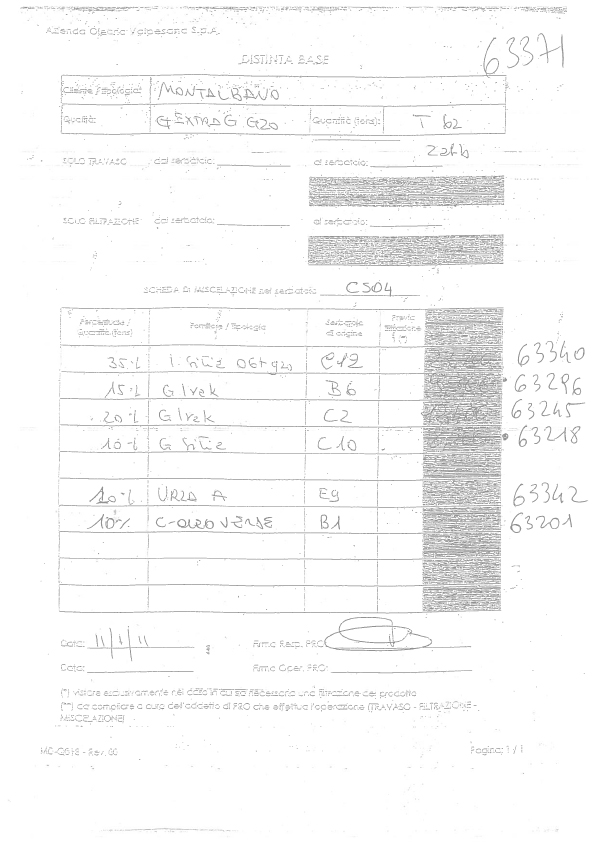

The finding of the secret recipes arouse suspicion. Investigators found several pages with names of customers, abbreviations for oil types and olive oil tanks. The documents described different percentages for different chemical components of the oils.

“We immediately had the suspicion that these recipes were a manual to produce illegal oil in large quantities,” said Colonel Luca Albertario, head of the Guardia di Finanza of Siena.

The accidental findings caused panic reactions in the otherwise quiet Monteriggioni. Lattanzio had been a Valpesana lab assistant for nine years at that point.

“After the first police raid, the company’s CEO ordered the destruction of some documents,” Lattanzio told us. “We were asked to stop noting down certain oils’ values and we were not allowed to unload certain oils in the tanks. Basically, some oils were supposed to just vanish from loading and unloading registries.”

Lattanzio felt increasingly more uneasy at Valpesana. “We were asked to saveinformation on the mixtures only on external hard-drives and to take them home with us,” he said.

“I said I wanted to know nothing about frauds. I told my colleagues not to talk about it with me.” Lattanzio warned his colleagues of “being cautious.” But, he said, “from the judicial investigation I discovered they thought of being untouchable. Some just and feared their boss, Francesco Fusi, and were following orders.”

Lattanzio’s warnings were validated. Shortly after the raid Siena’s public prosecutor Aldo Natalini started a judical investigation. In December 2011 Lattanzio quit his job and begun collaborating with investigators.

According to Natalini’s findings, Valpesana defrauded its clients in two ways: it lied about both the origin and the quality of its mixtures. The alleged fraud was about selling as “100 percent Italian olive oil” or “100 percent Greek oil” some mixtures that were made of oils of different quality and origins.

Lattanzio assisted investigators to understand the complicated chemical processes behind the possibly adulterated oils. He translated abbreviations and explained the seized recipes. Two examples illustrate what investigators consider fraud.

A recipe from January 2011 proves how Valpesana supplied “extra virgin olive oil” to an Italian brand – without using a single drop of actual extra virgin oil. In fact, to create the mixture Valpesana used 52 percent of virgin oil and 48 percent of a Spanish oil, called URZA-B, that according to Lattanzio was a deodorised oil.

Deodorised oil is an industrially refined oil that helps stabilizing the chemical values of the final mixture, making it possible to respect EU limits in those mixtures that could exceed the right parametres. The chemical values of olive oil can change over time for many reasons, for example if the oil is stored for too long. If you mix it with deodorised oil, it gets more stable. This way, the mixing of two inferior oils plus a deodorise can result in one oil of high quality. Until now, EU law considers this an illegal practice as well as considers illegal deodorised oil itself.

Olive oil is industrially deodorised to kill bad tastes and smells. The oil is distilled in an airtight, vacuum room at 200 degree Celsius. Through this process, however, oil loses certain healthy ingredients like Vitamin E.

Another recipe bears the name of a prominent Italian brand, Azienda Olearia Montalbano Spa. That brand has at least one product on the shelves of the supermarkets of the Rewe Group. Investigators seized four recipes of this brand in 2011. According to these recipes Valpesana sold 300.000 liter of olive oil to this brand as extra virgin from Greece, but the mixture was made of 30 percent Tunisian oil, virgin Italian oil and Spanish oil with unknown quality. ↓↓

The Stream to Germany

Valpesana would supplied incredible large quantities of Italian, Greek and Spanish oil to middlemen. One of these intermediaries – a bottler – is Oleificio Salvadori, who supplied the Rewe group in Germany with Valpesana’s mixtures.

Rewe group owns the Rewe supermarkets and Penny discounters.

In a response to our inquiry Rewe wrote that the company does not know from where it’s middlemen get their oil from. Rewe stated that all they expect from their suppliers is “the respect of our quality requirements, reviewed by the partners as well as our own quality management, in cooperation with reputable laboratories.”

Unannounced audits are also used to check on quality, claims Rewe. But the company does not scrutinize imported products from quality brands. “The quality control of name-brand products has to be performed – by law – through the respective manufacturer.”

Patrizio Salvadori, the CEO of Oleifico Salvadori, accepted a plea bargain because he appeared to be aware of fraud in one occasion, during a supply to a British client. Salvadori has been trading with Valpesana for a long time, supplying Rewe in Germany with their mixtures.

Investigators collected a number of evidences with which they confronted Salvadori in an interrogation asking for explanations. One of these is a phone call of 22 February 2012 he had with Valpesana’s CEO Fusi, while discussing a sample of oil he was not satisfied with.

The conversation continues and the two are complaining about a contract they have done with some clients but they are missing the right oil for it. At one point Salvadori gets angry and says “Let’s find this oil, because we have to create an extra-virgin. Or at least something that is close to an extra virgin. This oil you delivered is definitely risky.” Valpesana’s boss Fusi rebuffed Salvadori: “You know very well what you get for 1.88 Euros.”

An extensive survey of Spanish olive oil manufacturers shows that from harvesting to pressing the olives it costs 1.90 to 2.40 Euro per liter today. A few years ago the price has been just a little lower. That is not taking into account profits for the manufacturer and the middlemen as well as transportation.

The price that Salvadori and Fusi negotiated therefore gives very little or no margin at all for profits, if it were not for state subsidies that allow farmers to sell their oil for such a low price. In most of the German supermarkets olive oil sells for three Euros per liter, sometimes for even less than that. Companies like Valpesana can only survive by trading very large quantities of oil working with profit margins of a few cents per liter.

Salvadori told us that the price for Spanish olive oil was down at the time he and Fusi discussed the price on the phone – about 1,77 Euro per liter for wholesale traders. He added that he didn’t complain with Fusi about the mixture and quality of the oil but only about the taste.

Taste seemed to be very important to Salvadori. In fact, Salvadori asked Fusi in April 2012 to change the supply for his British client Princess. According to what Salvadori told the investigators, the oil he got was too bitter and his client wanted something sweet. Salvadori knew that this specific batch of oil was labelled as Italian but cut with Greek oil. That’s why he was charged guilty for contributory negligence in a commercial fraud case and pleaded guilty.

Salvadori told the investigators that Fusi told him the mixture was made with greek oil. „I didn’t think about his words too much because this specific oil is known to have a higher quality and is a very expensive product.“ When we asked him why he accepted a plea bargain, Salvadori said that his company and he himself “have never accepted a plea bargain for oil adulteration or for deodorised oil because such a violation of the law was never contested.”

Nevertheless, Salvadori’s criminal record was signed for fraud – to avoid the trial.

The oil Salvadori delivered to REWE was one of the best oils he got from Valpesana. “Not one of our deliveries to Rewe has ever been challenged,” wrote Salvadori. On the contrary: his olive oil ‘Penny Eigenmarke’ won an olive oil taste competition. “Our company sells more than 140 million liters of olive oil per year, to supermarkets in the whole world.” Never, he wrote, did customers or agencies find anything to complain about in their reviews and tests.

Salvadori also stated that the prosecutors didn’t seize any of his products during the Valpesana investigation. But that’s untrue. In May 2012 the prosecutors seized 108 tons of oil that was sold from Valpesana to Salvadori. Some of it was bulk oil for Rewe. Later the oil was all given back to Salvadori but 6.000 bottles had to be re-labelled and downgraded.

The main trial against Valpesana begins at the end of October in Siena. Three of the seven culprits got plea bargain at the pre trial. Among them was the head of Valpesana’s chemistry laboratory, who accepted plea bargain and got 23 months on parole. The remainder – including Valpesana CEO Fusi – will stand trial for the formation of a criminal organization with fraudulent intent and for the tampering of evidences.

Lattanzio still lives in Monteriggioni, only a few hundred meters away from Valpesana’s company site. He doesn’t regret quitting his job or cooperating with the prosecutor.

“The olive oil industry needs true reform,” he said. “New managers, who lead their companies in a sane way.” Lattanzio is now a young father of a daughter and works as a chemist for a pharmaceutical company.

Valpesana’s boss Fusi doesn’t talk to journalists since we interviewed him back in October 2012. Back then he believed that he did nothing wrong and saw himself as a normal part of the industry.

“I can assure you that Valpesana perfectly represents the extra virgin market in Italy and Europe,” he said when we confronted him with the accusations. His message: is that everyone does what they are doing. “Our work reflects the needs of our customers and suppliers.”